The Seven Senses

If you asked someone to think about their senses, most people would name the following five: vision, hearing, taste, smell, and touch. Often what is less familiar are the other two senses: vestibular and proprioception.

The vestibular system is part of the sensory system that controls the sense of balance and spatial orientation for the purpose of coordinating movement with balance. Examples include maintaining balance while learning to walk, holding objects, and turning pages of a book.

Proprioception refers to the sense of the position of parts of the body, relative to other neighbouring parts of the body. Focuses on the body’s cognitive awareness of movement. Examples of proprioception include stepping off a curb without looking at your feet and knowing how much pressure to apply when pressing an elevator button.

Sensory Processing

Sensory processing is the way our brain accepts, interprets and organizes information from our seven senses to create a response. No two people will react exactly the same way; everyone has their own unique response to sensory stimuli.

Sensory processing is automatic for most individuals. However, sometimes children have trouble organizing and responding to information from the senses, which can lead to sensory processing challenges.

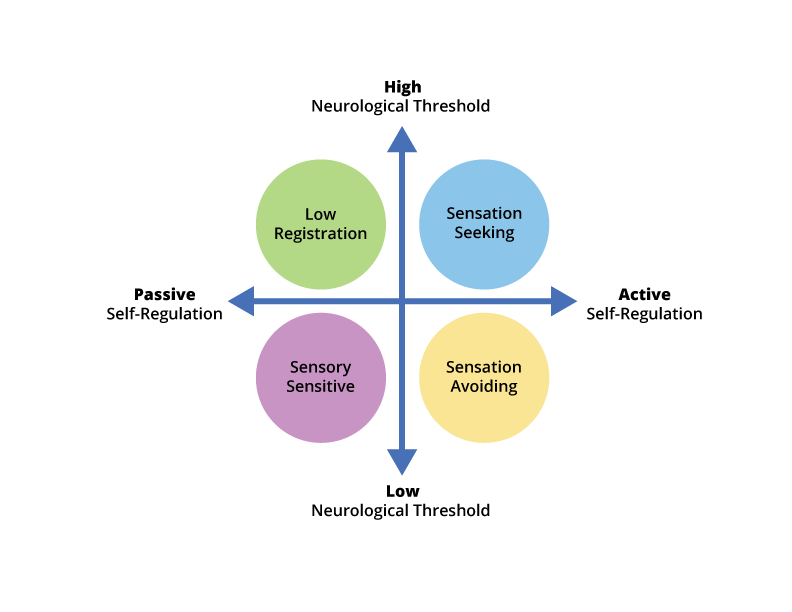

One common way of understanding sensory processing challenges is by using Dunn’s Four Quadrant Model of Sensory Processing. This model divides sensory processing into four patterns. These are: low registration, sensation seeking, sensory sensitive, and sensory avoiding. Sensory processing depends on the interaction between your child’s neurological threshold and their self-regulation strategies.

A Neurological threshold: Information coming to a child from the environment triggers activation of the children’s nervous system at a particular threshold. This threshold indicates how intense the stimulation has to be for the child to notice it and falls on a continuum from low to high. For example, children with low thresholds notice even low levels of input to the nervous system, while children with high thresholds require a greater level of input to notice the stimuli. Children with high thresholds may miss information that others receive because they need more input to notice something. For a child with a high neurological threshold, a teacher may have to say the child’s name several times as well as touch them on the shoulder to get their attention. However, one type of sensory input may be enough for a child with a low threshold.

Self-regulation strategies are the strategies a child uses to manage incoming sensory information. These range from active strategies to passive strategies.

A child with active self-regulation strategies will act immediately in overwhelming situations to either avoid (e.g., run away), compensate for (e.g., cover their ears) or seek more sensory stimulation (e.g., hold toys in their hands).

On the contrary, a child with passive self-regulation strategies might not react in an overwhelming situation. They typically do not respond, may shut down, or complain about the stimuli, but may become frustrated later in response to the stimulation which could be expressed as an outburst.

An Occupational Therapist may use an assessment known as the Sensory Profile 2 to categorize a child’s sensory patterns. In this assessment, the Occupational Therapist will seek information from the parent, Early Childhood Educator and/or teacher who will be asked to report on the child’s everyday activity and their responses to sensory stimuli. The information will be summarized to help you understand which pattern the child identifies with for each sense. These categorizations are important because they can help you and Occupational Therapists create a plan to accommodate your child’s sensory needs. For e.g., a child may have low registration for touch, but be sensory sensitive for sound.

Case Example:

To better understand each of the four patterns of sensory processing, we will use Ayub as an example. Ayub is a 6-year old boy in Senior Kindergarten.

Ayub loves playing at the playground, constantly jumping from high surfaces and running around. He enjoys climbing very high on the playground structure which makes his teachers and parents nervous. Further, while at the playground Ayub and his brother enjoy playing catch. Ayub’s brother gets frustrated with him as he often unknowingly throws the ball down to the ground rather than to his brother, and has trouble catching the ball.

Ayub is uncomfortable in the lunchroom as he often finds other children’s food smells offensive. When he notices these smells, he tends to run out of the room and refuses to go back inside. Additionally, he is sensitive to the noises of other children at lunchtime and will become frustrated in loud environments.

The Four Patterns of Sensory Processing

Ayub’s active movement behaviour at the playground may be classified as sensation seeking. He requires a lot of motion input and actively seeks out motion by climbing to high heights, jumping, and running.

Ayub’s body awareness while playing catch may be classified as low registration. Ayub does not have awareness of his force on the ball or his arm and body positioning to catch the ball.

Ayub’s sense of smell may be classified as sensation avoiding. He notices smells with a low threshold and avoids the situation by leaving the space.

Finally, Ayub’s sense of hearing may be classified as sensory sensitive. Ayub has a low threshold for noises as he becomes easily bothered by the noises of other children, but he does not avoid the situation. Instead he passively becomes frustrated.

Now that you know about each pattern of sensory processing, it is important to understand how this relates to each sense individually, and what can be done to accommodate your child’s specific sensory needs. There are tip sheets in this module that detail information and strategies to support sensory processing for each of the seven senses.