A short interview between Nicole Alphonse, Behaviour Services Consultant, Specialized Resource Home | Specialized Services Community Living Toronto and Kerry-Anne Robinson, M.Ed., BCBA, Clinical Director, Progressive Steps Training and Consultation.

What is ACT?

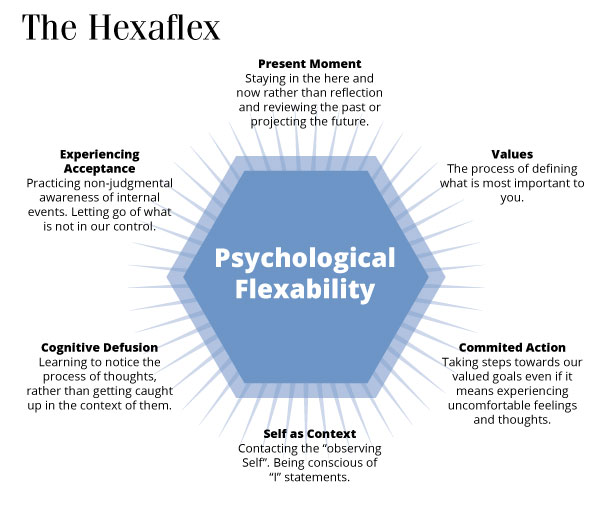

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) is a set of tools and strategies that can be used to help people to accept and make peace with events that happen day to day that are out of their control or cause negative feelings. ACT is aimed at helping people to commit to behaviours (actions) that bring

them closer to the things that are important to them. ACT utilizes a variety of exercises to help people experience the 6 core processes and to develop psychological flexibility. See ‘The Hexaflex’ diagram.

What is the ACT Matrix?

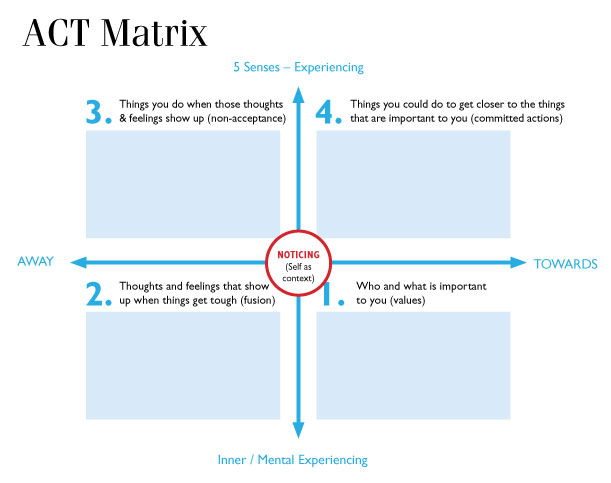

The ACT Matrix is a simple exercise designed to learn how to discriminate between our internal and external experiences. It also helps us identify behaviours that we may engage in that are unhelpful resulting in moving further away from the things we care about (values). Additionally, the Matrix helps us to identify actions that we can take to be more aligned with our values. In a nutshell, the ACT Matrix is an exercise to teach you psychological flexibility using real-life scenarios.

Components:

- The vertical line pointing up represents experiencing with the senses, also referred to as the present moment, and pointing down which represents our inner experiences, such as thoughts and feelings.

- A horizontal line intersects with the vertical line at 90 degrees to create four quadrants. The horizontal line represents our behaviour which either moves us toward our values (the right side) or away from our values (the left side).

- The lower right quadrant is for identifying who and what is important (your values)

- The lower left quadrant is for identifying unwanted internal thoughts or feelings that show up when things get hard (fusion)

- The top left quadrant is for identifying the specific behaviours that you do to avoid the unwanted internal thoughts and feelings (non-acceptance)

- And the top right quadrant is for identifying the specific behaviours that you can do to move towards what Is important to you (committed action)

The Matrix outlines how the 6 core processes of ACT work at any

given time. Refer to the hexaflex diagram for a brief description of the 6 core processes.

Do not worry too much about understanding the hexaflex and core

processes, for now we want you to become familiar with what ACT is

and how to use the ACT Matrix. Click below for a brief video.

https://neshnikolic.com/hexaflex

The main goal of the ACT Matrix is to learn how to take notice of our

thoughts and behaviours, and to align that with what is important.

This means that we can choose to engage in the actions that move us

closer to what we care about despite the negative uncomfortable

thoughts or feelings that we have. Filling out the Matrix allows us to

identify and sort through our thoughts, behaviours, and experiences.

It is a tool to help build mindfulness, self-awareness, and valued

living.

This may sound overwhelming and that Is okay! This is a new skill

that needs to be learned and requires practice.

ACT Matrix template

This may sound overwhelming and that Is okay! This is a new skill that needs to be learned and requires practice. We will walk you through a case study and show you how to fill out the Matrix step by step.