Materials Required:

- 2 puppets

- toy care and small drawing for the puppet show

- puppet theatre (optional)

- visual schedule outlining the schedule for this session

- rules board

- crayons, markers or pencils (one per child)

- scissors (one per child or enough for children to share)

- glue (one per child or enough for children to share)

- art activity sheets for “Getting Someone’s Attention” (one per child)

- “What I did in Social Skills Group” worksheets (one per child)

- “Getting Someone’s Attention” story books (one per child)

Schedule:

-

- Review the plan for today’s session by showing the children the visual schedule.

- When reviewing the schedule, point to and name the pictures in order (e.g., first we will sing hello, have a puppet show, etc).

- You may consider removing each picture as the activity is completed. You can create a pocket at the bottom/end of the schedule that represents “finished” or “all done”.

- Place the schedule in a visible and accessible place where it can be referred to throughout the session.

Visual Schedule Pictures

-

- Each session begins with a song that welcomes all the children and teachers to the group. Here are a few suggestions:

- Sing “Hello (child’s name), hello (child’s name), hello (child’s name), so glad you came today”. Repeat until everyone in the group has been greeted. Encourage the children to join in by waving hello and singing along.

- If age appropriate, create name cards/tags for each child and teacher. Hold up each card while singing the “Hello Song” above. After singing the child’s name give them the name card to hold. Once the song is finished, ask the children to put their name cards behind them. The children can use the name cards later in the session when completing the worksheet.

- You may also choose to use a “hello” or “welcome” song that you currently sing in your classroom.

- A rules board or a positive behaviour chart can help to provide a clear and consistent description of rules and expectations for the session. Decide on the main rules that will help the session run smoothly and help the children be successful in their learning. In our sample board, the rules are: raise your hand for a turn to speak, one person talks at a time, listen to others, sit on the carpet, keep your hands and feet to yourself, and have fun!Review the rules during each session. Have the children look at the rules, point to them and label them. Place the rules board in a visible and accessible place where it can be referred to during the session.

Group Time Rules

-

- OPTIONAL: Review the skill from last session. Ask the children if they remember what they learned in the previous social skills session. Can they recall the steps involved?For example, the previous skill was “When Someone Says Your Name” and the steps are:

- I have to stop what I am doing.

- I look at the person calling my name.

- Then I can answer by saying, “Yah, yes, or I’m here!”

- The puppet shows that you will be performing help to demonstrate the concept or skill for this session. At this time, you will be performing the ‘Appropriate Script’ which models the steps involved in getting someone’s attention.After the puppet show, have a brief discussion with the children about what they saw. Here are some sample questions you may want to ask:

- What was Jerome doing? (He was playing with a toy car.)

- How did Mona get Jerome’s attention? (She walked up to him and then tapped him on the shoulder.)

- What did Jerome do next? (He stopped playing, looked at Mona and answered her.)

Puppet show script – Getting Someone’s Attention

-

- At this point, you can introduce the social skill for this session by showing the steps involved in how to appropriately get someone’s attention. Refer to the “Step by Step Visuals” and show them to the children.

- I can walk towards the person.

- I can say their name.

- I can tap them gently on the shoulder.

- Then, I wait and listen for an answer.

We recommend keeping these visuals out so the children can refer to them during the puppet show that follows. For example, place them on the floor in the middle of the circle for all the children to see.

Step by step: Getting Someone’s Attention

-

- The second puppet show that you will be performing is a scenario where one of the puppets does not follow the suggested steps for ‘getting someone’s attention’. At this time, you will perform the ‘Inappropriate Script’ for getting someone’s attention.After the puppet show, have a brief discussion with the children about what they saw. Here are some sample questions you may want to ask the children:

- What was Jerome doing? (He was playing with a toy car.)

- How did Mona get Jerome’s attention? (She walked up to him and then tapped him on the shoulder and called his name.)

- Did Mona wait for Jerome to answer? (No, she begins to shake him and screams at him.)

- How do you think Jerome was feeling?

- The story helps to reinforce the steps and desired responses about ‘getting someone’s attention’. Read the story to the children. Let them know they will receive a copy of the story to look at later and/or to take home.

Book: Getting Someone’s Attention

-

- The group game is intended to give the children an opportunity to practice how to get someone’s attention. The following is a suggested group game:This Duck Duck Goose game has been slightly modified to match the steps for getting someone’s attention.

All of the children will sit down in a circle facing each other. They are now the “Ducks”. Pick one child to be the Fox. The Fox slowly walks around the outside of the circle, gently tapping the other players shoulders while saying “Duck” each time he/she taps. After a few times around the circle, the Fox selects a “Goose” by tapping a player’s shoulder and saying the child’s name (e.g., “Duck, duck, duck, Jasmine!”.

The child whose name has been called (otherwise known as the ‘Goose’) quickly jumps up and chases the Fox around the circle, trying to tag him/her before he/she can get to the spot where the Goose was just sitting. If the Fox succeeds in taking the place he/she is now safe and the Goose becomes the Fox. If however the Fox is tagged while running from the Goose, he must start the game again.

- OPTIONAL: The art activity focuses on the sequence of steps involved in getting someone’s attention. You can include this activity as part of the session or use it as a follow up activity to be completed another day.Please refer to the Art Activity sheets.

Art activity: Getting Someone’s Attention

-

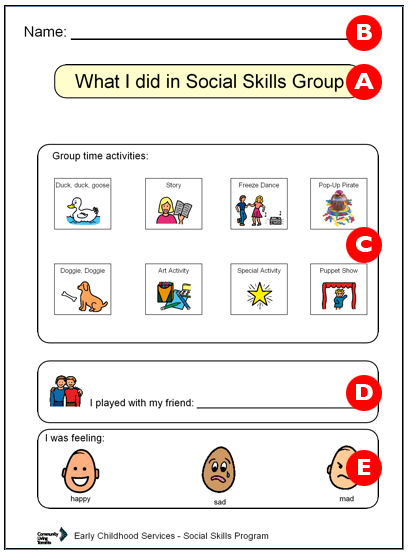

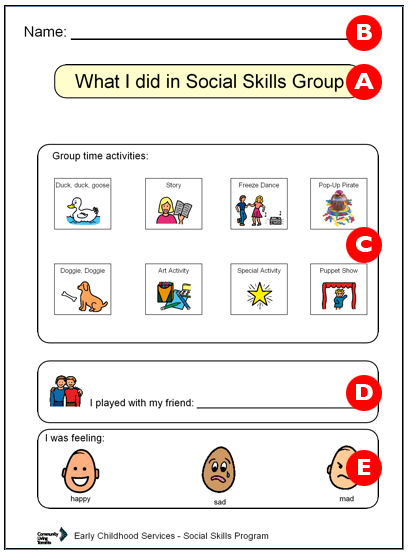

- Distribute the “What I did at Social Skills Group” worksheets to each child along with a marker, crayon or pencil. Once the children have all the materials, review the worksheet and point out what needs to be completed in each section.For example,

a) Point to the title box and read this to the children.

b) Ask the children to write their name on this line (point to the line at the top of the paper).

c) Review the pictures in the “Group time activities” section by pointing to the each picture as you label it. Ask the children to circle the activities from this session.

d) Here, ask the children to write the name of at least one other child they played or interacted with during the session.

e) Have the children identify how they were feeling during today’s group session.

* If you are using name cards or tags, ask the children to place them on the floor in front of them. The name cards can be used to help children to complete the worksheets by writing their own name, and the name(s) of a friend they played with during the session.

Once the worksheets have been completed, collect the writing materials and ask the children to place the worksheets in front of them. Let the children know they can take the worksheets home to share with their family and friends.

Worksheet: Getting Someone’s Attention

- Distribute “Getting Someone’s Attention” books to each child. Let the children know that they can bring the story home to read with their parent(s), family and friends.You may want to include a copy of the story at the book centre in your classroom.

- Sing a goodbye song to conclude the social skills session.

- Sing “Goodbye (child’s name), goodbye (child’s name), goodbye (child’s name), so glad you came today”. Repeat until everyone in the group has been greeted. Encourage the children to join in by waving goodbye and singing along.