Developing Functional Play and Adaptive Behaviour

Introduction

Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder often have challenges with functional play skills and adaptive behaviour (tasks associated with daily living). They benefit from environmental supports and direct instruction to develop their play skills and independent living skills. There are strategies and supports that incorporate direct teaching of play and other adaptive skills to develop essential skills. See Modules 3 and 4.

Developing Functional Play

1. Definition and Importance of Functional Play

Functional play can be defined as play with toys or objects according to their intended function (e.g., rolling a ball, pushing a car on the floor, pretend feeding a doll).

Play is a way children learn to make sense of the world. Functional play is a powerful tool for developing cognitive and social skills. Play develops a child’s problem-solving skills through the discovery of properties of actions and objects (e.g., hard/soft, fast/slow, and how things work together).

Functional play is also important in social interactions. Children interact with each other through play with toys, equipment, and action sequences. Sharing enjoyment in play develops a sense of connectedness with others.

2. How Children with ASD Play

Children with ASD may exhibit a range of play behaviours. The range of the play behaviours is dependent on the child’s level of development and the accessibility of supports and structure in his/her environment. From earlier to later developmental levels, these behaviours can range from:

- Appearing uninterested in objects, toys and peers

- Repeating actions with objects (e.g., spinning the wheels of a toy car, or lining up blocks).

- Limiting play sequences: only appropriate single actions with toys (e.g., shaking a maraca,pushing a car on the floor, or swinging on playground equipment).

- Creating more elaborate play sequences involving two or more actions with toys (e.g., putting a ball in a hole, hammering, building a block tower then crashing into it with a car, stringing beads, using a marker on paper, feeding a baby doll with a spoon).

- Linking related play sequences (e.g., putting the doll to bed, waking it up, feeding it).

- Displaying organized play (e.g., initiating play with an object, using it appropriately, putting it away and finding another object).

3. Why Play is Difficult for Children with ASD

This is not well understood. The possible reasons include difficulty with:

- Attending to functional play aspects of the toy or object

- Adjusting to novel or sensory qualities (e.g., noisy toys or those with certain tactile qualities)

- Imitating the actions of others

- Generating novel ideas about how to play

- Knowing how to initiate, sustain, and end a play activity (changing with the natural flow of play)

- Understanding how to share the enjoyment of play with others

4. Supports for Play Needed for the Child with ASD

Almost all children with ASD need support to develop their play skills. These supports might include:

- Setting up the environment so that the child is able to focus (see Module 2)

- Engaging the child in what interests him/her and can be jointly enjoyed

- Gradually introducing new toys and sensory experiences because some children need to be exposed to a new toy for a while before initiating a purposeful interaction

- Task analysis -Breaking play down into steps (see Module 4)

- Modeling how to play with the toy

- Guiding the child to play with a toy or piece of equipment and gradually fading support

- Encouraging the child to imitate his/her peers

- Providing visual supports so the child can be a more independent player (choice boards or mini schedules (see Module 2)

- Providing rewards or favourite play activities alternated with successful play attempts

- Creating desirable opportunities for the child to learn

- Generalizing play sequences into a social context (e.g., a teacher facilitating a game with a child and his/her peers)

Always provide positive feedback and reinforcement for appropriate play. If this is a new skill the child is learning, s/he will need more validation and higher praise at first. Remember, to see a behaviour or a skill again the child must be validated and reinforced.

Adapted from the Denver Model Treatment Manual, 2001

Teaching Adaptive Behaviours

1. Definition of Adaptive Behaviours

Adaptive behaviours are skills that support basic daily living functions (e.g., using a fork, putting on boots, blowing your nose).

Adaptive behaviours are usually sequences of movements put together to achieve a specific outcome (e.g., eating, dressing, toileting, hygiene activities, chores, and sleeping). These skills usually occur in the context of daily routines, in a particular place, and at a particular time each day.

Adapted from Steps to Independence, 1997

2. Difficulties with Adaptive Behaviours

Delays in learning adaptive behaviours can be caused by difficulties with:

- Initiating and continuing a sequence of movements (motor-planning challenges)

- Heightened awareness of sensory qualities (e.g., textures/tastes of food; feeling of clothing; sound /feeling of hair-cuts or shampoos)

- Focusing on a task

- Gross and Fine-motor skills

- Cognitive delays

3. How to Work with Adaptive Behaviours

The principles of OBSERVE, THINK, TRY are recommended.

Find a way to measure and record how the child is progressing. It is a good idea to keep the chart simple and handy.

The chart could be kept near where the skill is being taught so that staff can easily check off (e.g., on a clip board high on wall by the snack table with a pencil on string taped to it). (See Module 4, for more examples of charting).

Set up a way to communicate with other staff and the parents. Ongoing communication between the team members is imperative in successful teaching. Talk to staff and parents about strategies used, or create a communication binder or notebook to travel with the family. Implement the plan and record progress. Evaluate progress and alter the plan as needed. The child may not demonstrate signs of change immediately, so it is important to remain consistent with the plan for at least two weeks. The plan may need to be modified depending on the child’s progress within a reasonable amount of time. Set new objectives on a regular basis, or at least every 3 months.

4. Teaching Adaptive Behaviours

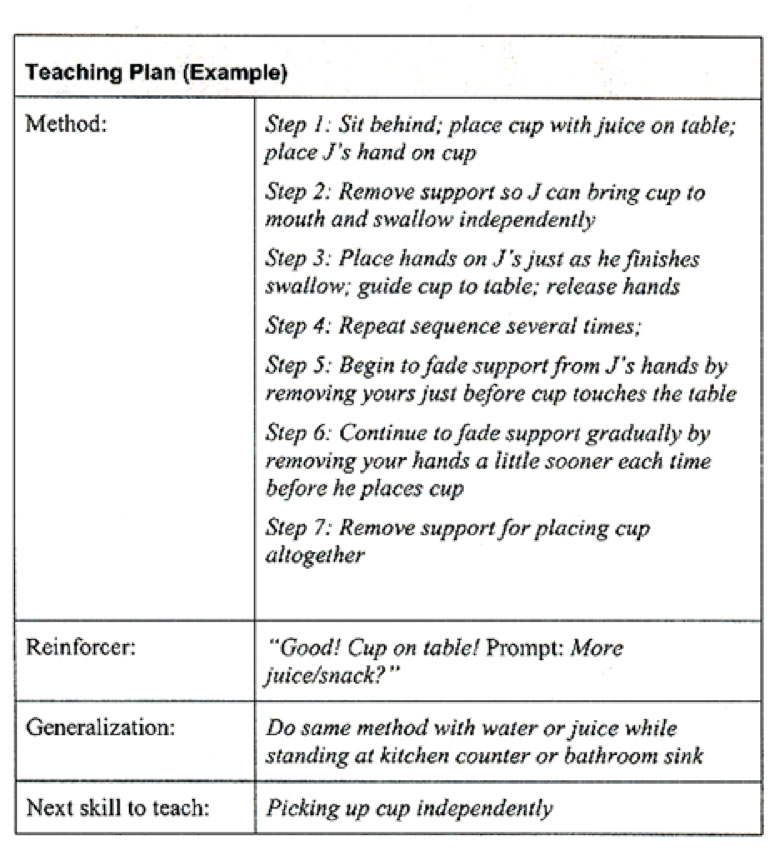

In order to help a child experience success, she/he must be provided with the right level of support and rewards. As the child progresses, the frequency of support/prompts and rewards can be gradually decreased. This helps the child to succeed by working in small steps towards the desired skill.

Consider the learning style of a child with ASD.

- May find it challenging to follow verbal directions and imitate

- Usually responds well to visual supports and physical guidance

Ways to help a child learn an adaptive behaviour skill:

- Teach within the natural routines when the skill is needed

- Teach the child to use cues from the environment (e.g., initial brief verbal instruction to get dressed, the sight of clothes in the cubby, a picture schedule)

- Reduce verbal cues (reduces reliance on adult presence)

For some children, modelling the task will be enough to help the child learn the task. For many children with ASD, once the initial direction has been given and a model has been shown, the child may require guidance to ensure success.

Sometimes it can be most effective to give and fade support throughout all the steps of a task. This “whole task” approach means that the child does the parts they can in the sequence and is prompted for the other steps.

In other situations, it may be best to focus on helping the child complete only the first step or the last step of the skill. From there, you can build on this initial success by focusing on the next step until the task is complete. These approaches are called, respectively, “forward chaining” and “backward chaining”. An example of backward chaining is as follows: first help Billy to put on his sock until the final step of pulling it up past his ankle. Next time, assist until the sock is barely over his heel, and let him complete the two final steps, pulling up the sock over the heel and past the ankle. In this approach, you are setting up the child for success. Remember to heavily praise the child for completing the task. This will motivate him/her to continue practising the new skill as the task gets more challenging.

If the child can match pictures to objects, you can make a picture schedule of some of the steps involved in certain skills (seen in Module 4). Place the picture schedule where the task normally takes place. Guide the child (as needed) to point to each picture to help complete the steps. Then guide him/her to do the step indicated. As the child progresses and moves through the steps independently, remove the steps s/he has mastered from the chart.

Keep the chart as long as the child needs support to go from one step to the other (e.g., a Velcro strip near the child’s cubby may have pictures of clothing items in the sequence. Guide the child to point to first picture, find the item, put it on, then turn over the card, and point to the next card, find the item, put it on, etc).

Try to provide a natural consequence as a reward for completing the skill (e.g., being able to go outside after getting dressed or drinking juice after fetching and pouring it).

Many repetitions may be needed to gain independence. The child receives support to complete what he can on his own. This gives the child a sense of mastery and reduces frustration.

5. Problem Solving

What About the Child Who Does Not Like to be Touched or Guided?

Children who do not like to be touched should be approached more slowly and gradually. Look for types of touch that the child does tolerate. Often firm, broad touch is more acceptable than lighter or more tentative touch, and it can help to relax a child. Some children prefer to be touched on the feet or back. Look for pleasurable ways and times in the day to provide touch experiences so that the child gradually accepts being touched. A good way to do that is through “sensory social routines” such as familiar songs and games that incorporate pleasurable touch experiences. These can be done at the beginning, end, and at various times throughout any activity.

Review

- Children with ASD often have delayed play skills.

- They benefit from direct teaching of play skills and additional supports for independent play.

- Children with ASD may have delays in learning adaptive behaviours or the skills of daily living.

- Adaptive behaviours can be supported and taught in a systematic way within the daily routines in which they occur, as well as in specific teaching sessions.