“I don’t want to go to bed! I’m thirsty! I need to go to the bathroom! I’m scared of the dark!” If you’ve heard your child repeat these phrases night after night, chances are you may be struggling with bedtime. Bedtime can be a nightly challenge for parents when your child resists going to sleep, or when she awakens in the middle of the night looking for mom and dad.

Understanding why children have sleep time difficulties

Sleep problems are very common in children of all ages. A child may experience poor sleep during a brief period in their life, like holidays, a stressful event, or illness. For some children, not being able to settle down to sleep may occur only occasionally and for others it may be more frequent.

Children who are well rested are generally happy, healthy and feel at their best. They’re able to learn, imagine, create, and socialize with ease after a good night of sleep. Research indicates that children (and adults) who are sleep deprived have more trouble controlling their emotions. In other words, the part of the brain that helps us to control our actions and our response to feelings is greatly affected by lack of sleep.

Children who do not get enough sleep may have difficulty waking up in the morning, may be irritable (ill-tempered), easily frustrated, or may fall asleep during play time or dinner. This may get in the way of their learning, their social interactions and their active involvement at school, or in their child care program.

By understanding the reasons children have bed time difficulties, you can help your child deal with her sleep issues so that she can become a happy, independent sleeper and bedtime will become a pleasant end to the day for the whole family.

There are a number of factors that can interfere with children falling asleep and staying asleep throughout the night. Here are some of the more common ones that you may be experiencing with your child:

- Separation Anxiety: For some children, bedtime means separation from their parents and the activities of the day. They are moving away from excitement and stimulation into darkness and being alone. Your child may feel anxious if you are not there, or if you try to leave her room and so she is unable to relax and sleep.

- Power Struggles: Power struggles are common from 18 months of age and on, as children begin to express their independence. Some children try to show this independence by resisting going to bed.

- Night Time Fears: Fears of the dark and imaginary monsters are especially strong for children between the ages of two to six years old. Although fears are common in preschoolers, intense fright, especially when accompanied by panic, is unusual and may be a sign that help from a professional is needed.

- Nightmares: Nightmares are quite common and most children experience them at some time or another. The child will awaken from the frightening dream and remember what happened quite clearly. Sometimes she can be comforted and settled back to sleep, but other times she may need extra reassurance to do so.

- Other common causes of sleep problems include:

- Not being able to relax without some form of help.

- Not being able to recognize that they are tired.

- Wanting more time with a parent (especially if the parent works outside the home).

- Physical environment. For example, the temperature may be too hot, or too cold, lighting may be too bright, or too dark, the covers may be too light, or too heavy, or sounds in the room or home may be too noisy.

- Stress or worries about child care, school performance, friends, family conflicts, or other problems in their lives.

- Inappropriate napping. A child may have very long, or too many naps during the day.

- The presence of parents, brothers, or sisters in the same room who may be providing distractions such as coughing, snoring, talking, etc.

- Parents who are over-anxious themselves and may be constantly checking in on their child.

- Children with special needs. Research indicates that half of all children with special needs experience some kind of sleep difficulty.

Setting the Stage for a Good Night’s Sleep

There are many steps you can take to deal with your child’s sleep problems. We’ve already discussed the most important first step which is recognizing the possible cause of her sleep difficulties. The next step is looking at what you can do before your child’s bedtime to help ease her transition into sleep and help the routine run more smoothly.

Decide on a bed time

Decide on a specific time for your child to go to bed and try your best to stick to it everyday. There may be days when you can’t and this is okay as long as you get back on track with a daily, consistent schedule. Getting your child to bed at the same time every night provides her with a predictable routine. Keep in mind that you can’t force your child to fall asleep, but you can enforce the rule that she must be in her bed at a set time.

Also, it’s important to have consistent wake up times as well. If you don’t, this may make it more difficult for your child to go to sleep at night. Establishing a regular wakeup time will again provide your child with the structure and predictability she needs in her daily routine.

Establish bedtime rules

Children thrive on structure and order. They need rules in order to understand what is expected of them. This is especially important at bedtime. Establish clear, simple rules and review them with your child regularly. If you stick to these rules on a daily, consistent basis, children will accept the structure and will be more likely to follow the rules. Examples of bedtime rules might be: “No bouncing on the bed”, or “No drinking milk in bed”. You can use real photos or picture symbols to provide your child with a visual reminder to reinforce the rules.

Set up the room

Make sure the curtains or blinds in your child’s room do not let in too much light – this will help prevent your child from waking up too early in the morning. Keep lights dim in the evening as bedtime approaches. Also, check the bedroom temperature. It should be neither too hot nor too cold. Reduce any loud, or distractable noises around your child’s room. Consider soft music, or the soothing sounds of an air filter or fan, bubbling fish tank, or recording of water falls to block out background noise that might disturb your child.

Provide choices

Whenever possible, allow your child to make choices within her routine. For example, she might choose which pyjamas to wear, which stuffed animal to bring to bed, or what music to play. This gives your child a sense of control over the routine.

Allow a comfort item

Allow your child to take a favourite teddy bear, doll, toy, or special blanket to bed each night, so she has something with which to cuddle. This can also help comfort your child and give her a sense of security, or being safe.

Avoid sugar and caffeine

Try to limit the amount of caffeine and sugar your child eats or drinks before bedtime. Beverages such as colas and chocolate contain sugar and caffeine and may be a factor in your child remaining awake.

Consider effects of medication

Find out if medications are contributing to the problem. Talk to your doctor about any medications your child is taking. Some of them have a stimulatory effect and make it harder for children to settle down to sleep.

Cut out afternoon naps

Cut out afternoon naps if they are not needed. If your child does not seem tired at night and takes a nap during the day, either eliminate the nap time or reduce it to only 30 to 60 minutes.

Encourage exercise

Make sure your child gets enough physical activity during the day. Exercise, as well as fresh air, should be part of your child’s everyday routine. It’s as important as any other part of your child’s day. Ideally, this active time should not be too close to bedtime, as this may excite your child and make it difficult for her to fall asleep.

Schedule play times

Try to schedule daily play times with your child fairly close to the time she goes to sleep. This may help to prevent her fighting you at bedtime just to get your attention. Choose a quiet, relaxing and interactive activity that you will both enjoy. If she prefers to play alone, or you have something to do yourself, offer her an activity such as blocks, books, or puzzles.

Encourage relaxation

Help your child release her physical tension by stretching and relaxing her body in a variety of fun ways. Try these relaxation strategies with your child: breathing in and filling up like a balloon, slowly raising your arms and legs one at a time as if they are very heavy and then letting them drop back quickly, or wrinkling and then relaxing your face. Providing your child with a gentle massage will also help her to relax.

Establishing a Consistent Bedtime Routine

Sometimes parents don’t have much energy left at the end of a long day. Creating a consistent bedtime routine can help make this time successful and relaxing for both you and your child. Keep in mind that a bedtime routine might take 30 – 60 minutes. Here’s an example of a routine Jenny and her dad follow each night:

- Dad gives Jenny a 5-minute warning before the actual bedtime routine starts, so Jenny can finish playing and tidy up her toys.

- Dad gets the bath ready for Jenny. She gets to play in the bathtub for about 10 minutes.

- Jenny and her dad have a healthy snack such as yogurt or warm milk and sugar-free cookies. Dad remembers to avoid offering any caffeine or sugary foods and beverages.

- Jenny brushes her teeth.

- Jenny uses the toilet.

- Jenny puts on her pyjamas and gets to choose a stuffed toy to cuddle.

- Dad sits with Jenny in bed and reads her a book.

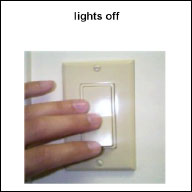

- When the story is finished, Dad says goodnight to Jenny and turns off the light.

It often helps to use a picture board to show each step of the routine so your child knows exactly what to do next. Here are the pictures that Jenny’s dad uses every night:

A Word of Caution

If your child remains highly upset despite your repeated efforts to deal with her sleep difficulties, consult with your paediatrician, or an early childhood professional. Consider getting help for your child if:

- She has sleep problems after you have tried an approach consistently for one month or longer.

- She is very sensitive and becomes upset over whatever you do to try to get her to sleep.

- She appears traumatized by the whole experience.

- She shows signs of a medical or physical condition that you think might be interfering with her sleep.

You may want to try keeping a Sleep Diary. A Sleep Diary allows you to record information from every bedtime that will enable you to see any unusual patterns of sleep. Take a look at the For More Information box for details.

Also, you should consider getting help for yourself if you have difficulty following through with a “sleep plan” once you have created one and/or you are negatively affected by your child’s sleep habits (e.g., exhaustion, anger, resentment towards your child, spouse, or others). You are the expert when it comes to your family and child. If you have a concern, trust your instincts and find someone trained to help you.