Personal stories can be a helpful tool to build resilience and self-regulation skills. With the help from an adult, children review these stories ahead of time to prepare them for new events, changes to their usual routine or to help them manage a social situation.

Personal stories can be used to:

- describe social situations that are new or difficult

- increase awareness of a situation

- provide suggestions about what to do in the situation

- give perspective or understanding on the thoughts, emotions, and behaviours of others

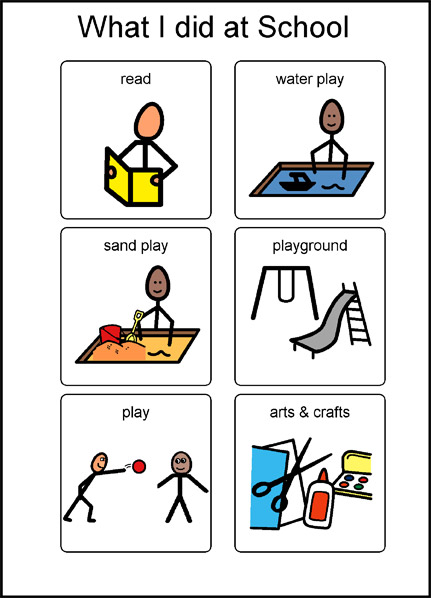

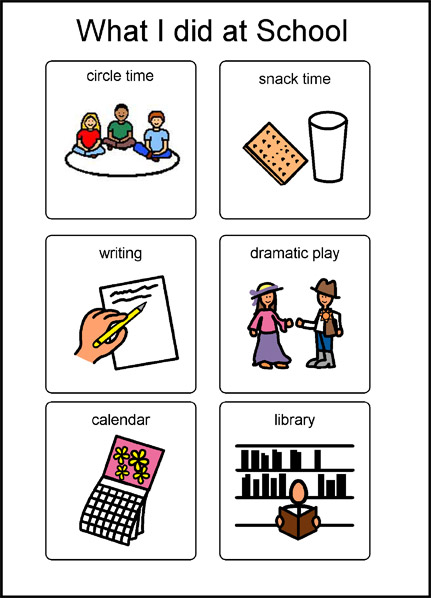

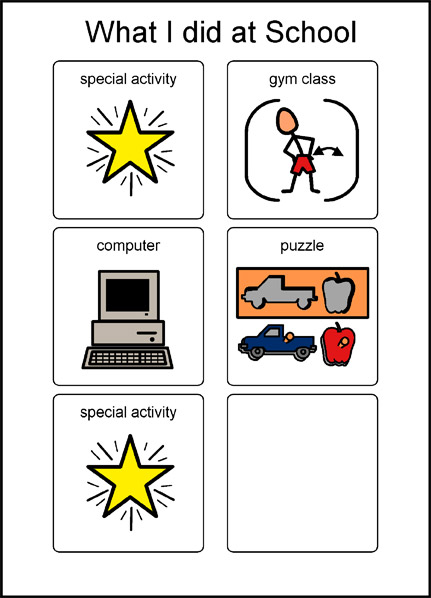

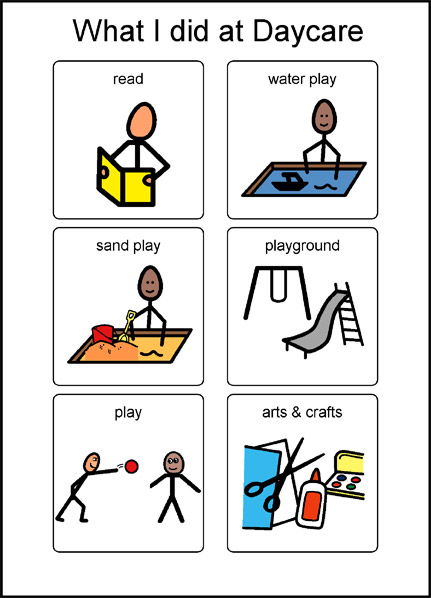

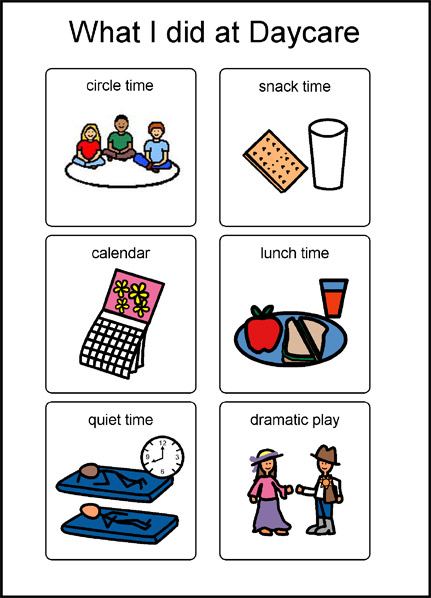

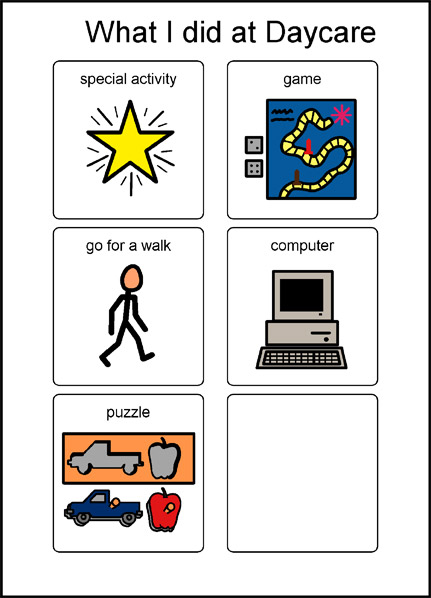

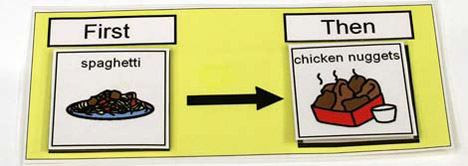

Any child can benefit from using a personal story. You can adjust the language, length, content and format for the child and situation. For example, for younger children you can use visuals such as photographs, drawings, or other pictures to support the written story. Incorporating elements of culture and identity into the story will help to add comfort and familiarity. Personal stories can also be recorded on an audio or video device to help children who learn best in this way.

When can I use a personal story?

- To prepare your child for new events and experiences

A personal story can help prepare your child for new events or stressful situations by showing them what will happen and what they can do. For example:

- asking a friend to play

- going to a doctor’s appointment

- having a visitor at home

- entering an early learning program

- To teach social skills

A personal story can help your child learn what to do or how to respond in a variety of social situations, such as:

- asking for a toy from another child

- keeping hands to self while waiting in line

- To teach a new skill

A personal story can be used to break down and teach new skills, such as:

- using the washroom

- taking turns during play

- crossing the street with an adult

How do I create a personal story?

In a personal story, the situation is described in detail with the focus on important social information such as what others might think, feel, or do. Descriptions about what to do in that situation are provided to your child.

Personal stories are written from your child’s perspective, using positive language in the first person (“I”), and in the present tense.

Correct: I sit quietly on the floor during story time.

Incorrect: Adam must not talk during story time.

When writing a personal story, make sure that you only mention what your child should be doing, rather than what he should not be doing.

Correct: I tidy up when I’m finished playing.

Incorrect: I don’t leave a mess after I’m finished playing.

Before writing a personal story, be sure that:

- It focuses on teaching one skill.

- You have talked to other people in your child’s life to get their input.

- It is written at your child’s level of understanding and has visual supports (such as pictures), if necessary.

Sentences in a personal story

Many personal stories start with an introduction, usually stating the child’s name. The following list describes the types of sentences that could be used when developing a personal story.

- Descriptive sentences explain the situation by answering the “wh” questions – where, who, what, when, and why.

- Perspective sentences describe opinions, feelings and ideas related to the situation.

- Affirmative sentences enhance the meaning of other statements to reassure the person.

- Cooperative sentences identify what others will do to support the child.

- Directive sentences suggest what the child could do (must be positively stated).

- Control sentences identify strategies that children can use to remind themselves how to behave. Often, a child (with the support of an adult) adds this sentence after reviewing the story.

Here’s a sample personal story:

My name is Matthew. (introduction)

I love playing with the big, yellow truck. (descriptive)

Jonathan likes to play with the yellow truck, too. (perspective)

When Jonathan is playing with the truck, I can say, “Can I have a turn, please?” (directive)

I wait until he is finished with his turn. (directive)

It is OK to wait. (affirmative)

My mom will help me stay calm while I wait for my turn. (cooperative)

My mom is happy when I wait for my turn. (perspective)

When Jonathan is finished, it is my turn. (descriptive)

I have fun playing with the truck. (descriptive)

I can remember to ask Jonathan for a turn and to wait. (control)

Here’s a sample personal story for a younger child:

My name is Sadia. (introduction)

Mommy drops me off at my program. (descriptive)

I like when she kisses me bye-bye. (perspective)

It’s okay for me to play and have fun all day. (affirmative)

Mommy comes back for me and takes me home. (descriptive)

I can look at Mommy’s picture, if I’m missing her. (control)

How do I use a personal story?

Once a personal story has been created, you can go over it with your child on a daily basis, until they are familiar with it. It is important to introduce and practice the personal story before the challenging or new situation occurs so they can be prepared. For example, if your child is currently working on a story about staying safe when they cross the road, you can review the story right before going for a walk to remind them what might happen and how to respond.

If the personal story is being used to teach your child new skills, provide them with opportunities to practice the steps to the skill. Go slowly and allow enough time for the child to transfer the skill from a story to “real life”.

Play is a wonderful way to connect personal stories to real life practice. If your child is not interested in books or responds more to “hands on” learning activities, you can tell them a story during play. For example, to prepare your child for going to see the doctor you can show them a play medical kit and allow them to act out a doctor’s visit.

What if it’s not working?

It is important to monitor whether the personal story is useful. If your child has not become more comfortable with the situation after two or more weeks of reading the story, it might have to be changed.

Ask yourself:

- Is the story too long or wordy? Is it confusing?

- Is it written at the right level for my child?

- Should visuals (pictures) be included?

- Does it focus on the behaviour you want to see?

Personal stories, when written and used well, can be very helpful tools in supporting children when experiencing new or challenging situations.

References:

C. Gray, (2010). The New Social Story Book, Future Horizons

C. Gray, (2000). Writing Social Stories with Carol Gray, Future Horizons