Setting the Stage for Learning

Introduction

Creating a successful learning environment for children with ASD may require adaptations in the following areas: physical environment, visual supports, transition strategies, schedule and routines.

Children with ASD in Group Child Care Settings

An inclusive philosophy is reflective of society’s view that all children have the right to equitable opportunities in education. While there is much variation with respect to strengths, abilities, functional levels and challenges among children, preconceptions should not be a barrier to inclusion as all children benefit from being a member of a diverse group. Inclusive settings can be beneficial for all children in the classroom.

Benefits of Inclusive Settings

- Chances to learn by interacting with other children of similar ages

- Time and support to build relationships with other children

- Chances to practise social skills in real-world situations

- Exposure to a wider variety of challenging activities

- Opportunities to learn at his/her own pace in a supportive environment

- Chances to build relationships with caring adults other than parents

- Opportunities to build friendships

Benefits of inclusive programs for typically developing children include:

- Increased appreciation and acceptance of individual differences

- Increased empathy for others

- Preparation for adult life in an inclusive society

- Opportunities to master activities by practising and teaching others

- Opportunities to build friendships

Considerations in Group Settings

Physical Environment:

Children with ASD benefit from stability and predictability within their environment. When changing or moving furniture, keep in mind that some children may need help and time to adjust to change. Changes can be made but may need to happen gradually.

Space

- To reduce running and wandering behaviours, provide smaller, more contained spaces.

- To assist children with identifying and focusing on what to do in a specific space, provide spaces that are distinct from each other for different types of play.

- To help define spaces, use shelves, furniture, and on a carpeted area, further define by placing individual mats. Create a calming corner using portable furniture for children to have quiet time.

- Reduce the amount of visually-distracting materials by keeping the classroom clutter-free.

- Keep artwork in one spot such as a bulletin board outside of the classroom rather than scattered throughout the room.

- Look for opportunities to provide natural lighting and subdued wall colours.

- Add sound-absorbing materials such as plush furniture and carpeting (where permitted).

- Have play areas that are set up for individual play, pairs, small group play, and large group play.

Materials

- Use appropriate seating which may consist of traditional chairs and tables, or more supportive seating such as a Raylax chair or Howdahug chair that promotes focus during individual or group times. Traditional chairs should allow the child to sit with good posture, have feet flat on the floor, and hips, knees and ankles at 90 degrees. Tables should allow the child to sit with elbows about 1-2” below the table top. In some cases, a chair with arms may provide additional security and boundaries for a child to help with sitting and attending.

- Promote relaxation, security, and ways to self-regulate. For example, beanbag chairs, large overstuffed pillows and child-sized rocking chairs may be placed in some spaces. A small tent with pillows inside and heavy quilts on top may offer an opportunity for brief respite from noise or others’ activity. Sensory materials such as rice bins, playdough, and tactile boards can be calming for some children.

- Provide for physical activity using heavy objects to lift, carry, or push. Schedule use of these materials regularly and between activities that require focused attention as a way to regulate emotions and prevent disruptive behaviours before they happen..

Visual Supports

Adults rely on visual helpers every day such as calendars, day timers, street signs, grocery lists, maps, and so on. Visual cues in the environment allow planning, organizing, and independence. Visuals are equally important to children because they are just beginning to learn how things work in the world.

Why do visual supports make it easier for children to understand and communicate?

- Words “disappear” right after we say them but visuals hold time and space.

- Visuals direct attention and hold attention.

- Visuals allow more time to process the information.

- Visuals assist in remembering.

- Using the same words every time a visual is shown teaches the child those words.

Anything we see that helps us with communication by giving us information for our eyes is a visual support. The type of visual that works best with each individual child depends on what is meaningful to the child. The most widely-recommended visuals are those that are used to provide children with information.

For example, labels placed around the home or classroom help to inform the child where to find and where to put materials. Rules provide your child with clear expectations. Other types of visuals that give information in a logical, structured and sequential form consist of schedules, mini-schedules, and “first/then” boards. Activity choice boards allow the child to make selections during their play.

The previously named visuals can be presented in several formats, depending on the child’s level of understanding. Ranging from most concrete to most abstract, possible visuals are:

- Objects – would be considered to be the first level of visual representations and would include the actual objects (e.g., for some children, seeing a sandwich in their parent’s/teacher’s hand tells them “It’s time for lunch.”)

- Colour photographs – would consist of coloured photographs of concrete objects (e.g., for some children being shown a photograph of a bus means “We’re going to daycare” or “We’re going home.”)

- lack and white photographs – would consist of the same photographs but in black and white

- Colour line drawings – picture symbols that are often used with children who are able to understand at this level of abstraction

- Black and white line drawings – also picture symbols and serve the same purpose as coloured line drawings

- Miniature objects – smaller versions of the objects

Tip: Remember to place visuals at the child’s eye level.

Preparing for Transitions

For many children, routines and structure are important because they provide a sense of security. Even slight changes in the usual routine can be highly upsetting. Preparing for transitions and having consistent routines help children to cope with change.

Children may have difficulty making transitions for many reasons. Here are some examples:

- Change is unexpected For example, weather prevents children from going out for regularly scheduled outdoor play.

- Current activity is enjoyable For example, child does not want to stop present activity for another event.

- Dislike or fear of the next activity For example, child knows what the next activity is and does not like it or is afraid of it, so resists getting ready.

- Next activity is enjoyable For example, child leaves present activity early in attempt to start enjoyable activity before it is time.

There are two main types of transitions:

- Daily: Major transitions during the day for young children usually involve sleep, mealtimes, or changes in the environment/location such as:

- From one activity to another

- Indoor to outdoor play

- School to home

- Life These are transitions that occur once in a while (e.g., starting a new job, having a baby, or moving). Children need extra care and attention during these times because change can be upsetting and frightening to them. For example, at daycare a child may be moving into another classroom with a new teacher and new children or a child may be moving to a different house.

Strategies to help a child make transitions:

Provide verbal warnings

Use warnings that a transition is about to occur. For example, “It is almost time for lunch.” The transition can be made concrete by setting a timer or counting down from ten after giving the warning.

Fidget Toys

If a child is finished with an activity but needs to wait for another one to begin, playing with a fidget toy (e.g., squishy ball) can help him/her keep busy. Experiment with a variety of fidget toys and choose ones that do not make noise and that the child is able to keep in his/her hands or pocket.

Transition Objects

Try using an object to signal that a new activity is about to begin. For example, if the child is playing and it is almost outdoor play time, bring the jackets into the room within sight.

Music

Songs are a fun way to signal that the current activity is about to end and a new one will be beginning. They help children learn routines and improve language and memory skills. Try using the same tune and changing the words for different activities. This will make it easier for children to remember the song and join in the singing. Learn more about transition songs by visiting the Creative Circle Time: Music, Stories and Games Workshop.

Visual Cue

To gain children’s attention, turn the lights off and on or say, “Put your hands on your head.” Once you have the children’s attention, begin the transition by singing, “It’s time to tidy up. Tidy up. It’s time to tidy up!” The song could be followed by two handclaps before turning the lights back on and then the children start to tidy up. This combination of strategies works because gestures and songs catch children’s attention.

Visual Schedule

Using objects, photos, or pictures to show a child the order of activities that are planned can help him/her understand what is going to happen next. Here is an example of a visual activity schedule.

Create visual schedules using photographs, pictures from magazines, or the Visuals Engine on this site. When first using a visual schedule, include one or two transitions. Gradually add more, up to a maximum of six or seven pictures in one schedule, based on the child’s developmental level.

To help a child understand when an activity is finished, attach pictures to a piece of bristol board using tape or velcro. As each activity is finished, a child can remove it from the schedule and put it in a small box or envelope labeled “finished”.

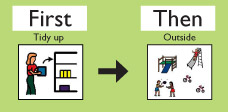

For some children you may want to have a full visual schedule of the day on the wall for reference. For transitions you might want to have a separate one that shows what is ending and what is starting. For example, “First tidy up then go outside”. Using a “first/then” visual to break down the immediate expectation can help the child understand what is coming next. This can also help the child to focus on the transition and what he/she needs to do.

Schedule and Routine

Schedules, predictability, and routine are essential for a child with ASD to function well, particularly in a group setting. Keep in mind the following:

- Provide consistent and frequent use of visual schedules of the daily routines and activities.

- Maintain a routine that does not vary much from day to day, especially when a child is new to the program.

- Ensure that the location of materials and equipment is consistent.

- Maintain an initial consistency in the staff the child will encounter daily to help establish routine.

- As the child becomes more comfortable, introduce small changes gradually to help him/her develop some flexibility. Examples could be changes in routine, place, and staff, using visual supports and schedules to cue the changes to the child.

- Provide a written individual schedule for the child with ASD, showing what s/he will be doing and with whom. Post this where it can easily be seen by staff to maintain consistency and structure for the child.

- Provide consistency for staff as well. Provide a written schedule of who will be where, doing what.

- Schedule routine time for staff to plan and communicate about the needs of a child with ASD, with parents and consultants as needed or available (see Module 8).