Vision

“From a dream comes a vision” J. Assinawai

OUR VISION IS THAT EVERY INDIVIDUAL ON A FIRST NATION WILL RECEIVE SUPPORT AND SERVICE FROM HIS/HER PEOPLE AND HAVE THE OPPORTUNITY TO RETAIN TRADITIONAL VALUES AND LIFESTYLES TO PROMOTE BALANCE IN HIS/HER LIFE. ALL PEOPLE WILL BE VALUED AS THEY ARE, AND SUPPORTED TO EXERCISE THEIR RIGHTS, INCLUDING THEIR RIGHT TO MAKE CHOICES, DECISIONS, AND PLANS THAT AFFECT ALL ASPECTS OF THEIR LIVES.

A preface to the teachings of the Medicine Wheel

There is a belief that everyone with a developmen- tal disability has access to services and supports. This is true for those individuals who reside near, or in metropolitan areas as well, but, for those in rural and remote areas, this is not the case.

Individuals living in rural and remote areas have difficulty accessing services and supports, mainly because they are not available, but also because there is no organized group available to advocate for those very services and supports. There is also a matter of a lack of fluency in the English language, for some individuals and their family members, living in the northern communities of the province.

The lifestyle/culture in First Nations communities is uniquely different and generally more accommo- dating of people with a difference than non-native communities. To this end many families have kept their children and young adults at home in a variety of situation. Only when the community can no lon- ger accommodate the person, and there is a crisis either in the family or in the community, do outside organizations become involved.

The individuals and communities that receive ser- vices and supports from outside their home commu- nities must often learn to adapt their ways (culture) to fit with the situation that best meet their needs. It is a cultural shock with a relearning of a new cul- ture/language and understanding that must occur.

There are services in some communities which came as a result of family members and health/ social workers advocating for services. Acquiring funding for services is/was not easy, because of the federal responsibility for native communities, and providing services for developmentally disabled individuals is deemed to be a provincial responsi- bility. Provincially funded services to native com- munities are usually cost shared with the federal government as part of the 1965 Welfare Agreement, which is bilateral agreement between the federal and provincial government. The Developmen- tal Services are not included in the 1965 Welfare Agreement, which is why it has been difficult to access funding. Responsibility for the provision of services and supports to individuals with a develop- mental disability belongs to the provincial govern- ment whether, or, not they are residing on a First Nations Community. The provincial government does now provide funding to native communities to provide services and support to developmentally disabled individuals.

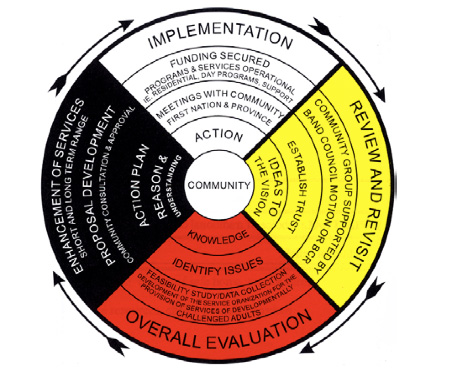

This booklet has been developed to ensure that everyone understands their rights, so that individuals with a developmental disability can be cared for by people who understand their culture, beliefs and language. This booklet also includes the Person- Centred Plan (PCP) process which we will call the Individual Life Plan (ILP), as well as suggest a path to follow to set up an advocacy group and accountability structure to access the services and supports that are needed by First Nations people, throughout the province.

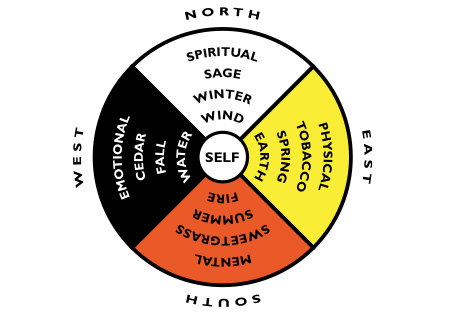

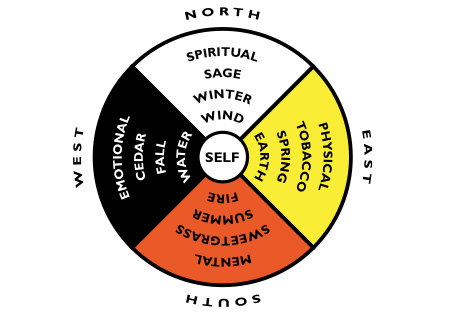

All Beginnings Start In The East

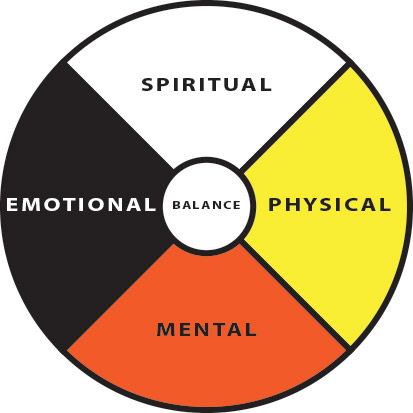

Teachings start at the centre, reflecting balance and harmony. The goal is balance with environment, spirituality, self, community and the natural world. Although these core teachings are universal to many First Nations (Aboriginal Peoples), it is recom- mended by the consultant developers that this wheel be recognized only as a guide. Consultation with community, Elders and Spiritual advisors is recom- mended to personalize the wheel to your needs.

Philosophy

In the eyes of the creator, we are all created equal. With this in mind, the programs we deliver will be based on this, and therefore we will treat the participants of our programs with respect, caring and equality.

We will deliver our programs in a holistic manner, always considering the four elements (physical, mental, emotional and spiritual well being), which will work together to create balance in a person’s life. Our organization will deliver programs and services to persons rather than clients, who will be treated in a manner that each of us would like to be treated. We will give participants freedom of choice to live, to grow, and to play in harmony and dignity in the community. – WAACL-JA

CODE OF ETHICS-VALUES

Humility

absence of sense of being superior to clients or employees, valuing individual equality, recognizing that everyone has a place in life; refraining from intimidation to clients and fellow employees.

Honesty

conducting oneself in the community and workplace in a responsible and honourable manner through truthfulness, fairness and sincerity.

Truth

speaking from the heart, and honouring the beliefs of others.

Respect

understand that the circle of life is sacred, that we are all part of creation, showing respect to individual beliefs and tradition, and for one’s own being and that of others.

Bravery

recognizing that other’s views may differ from ours, and honour the difference with the understanding that we are all one people, and have a right to freedom of beliefs and traditions.

Love

unconditional love for each other for who we are, and what we have to offer, with no conditions based on race, creed, or colour, and always looking for the beauty within each person.

Wisdom

using what we have learned in a meaningful way, and using past experiences to promote our growth, and the growth of others, to be kind, good, caring people.

MAKING SERVICES WORK FOR PEOPLE (MSWP)

In 1997, the Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services came out with a new framework to people with developmental services. The new frame- work contained nine goals, and communities were encouraged to focus on initiatives to reach these goals. The following is a synopsis of the document.

- Individuals and families throughout Ontario will have access to a consistent range of core services for children and developmental services.

MCCSS policies relating to MSWP also apply to native people. It is recognized that models for services delivered to native people may be designed differently, but must achieve the same goals of effectiveness. The process/outcomes which emphasize self-reliance, self-administra- tion, and programs and services appropriated to First Nations communities, must be consistent with the Aboriginal Policy Framework.

- Those most in need will receive essential supports.

Residential service is considered essential and is ideally located in the individual’s home community, close to their family. At the present time individuals are taken from their home communities when they are in need of a residence, or when the family can no longer provide care and support.

- Families and individuals will receive supports earlier.

Providing support, such as, respite care or a day program for the individual, will give families strength to care for the individual. A day program would teach basic skills to the individual and would decrease dependency on the family to a certain extent.

- Families and individuals will have easier access to services.

Access to a coordination of services would make services more readily available. Some areas in the province have service coordination that some First Nations people are already linked with.

- Families and individuals will receive services that respond to their needs.

Flexibility in the design of programs make them more adaptable to change, and give indi- viduals and families greater control in the types of services and programs they receive.

- Families and individuals will be served by local systems that make the best use of resources.

Making the best use of resources will enable a community to serve more individuals. Resources does not only mean financial by also community resources.

- Local systems will have lower administration costs.

Spending less on administration will result in more resources going towards program needs.

- Families and individuals will receive services that lead to less reliance on government funded services.

The government encourages cooperation be- tween community groups, such as volunteers, religious institutions, family networks, etc. to decrease reliance.

- Families and individuals will receive a coordinated set of services funded by the Ministry and Community and Social Services and other funders when necessary.

Individuals and families who require services funded by M.C.S.S.; or other non M.C.S.S.

funded organizations, will have a coordination of services involving partnerships with com- munity organizations.

Keeping in mind the nine goals of Making Ser- vices Work for People, supports and services for our people can be designed in a way which will meet our unique needs. We must design our programs to meet the holistic needs of the individual. The physical, mental, emotional and spiritual needs required to promote balance within ourselves have to be considered. Devel- opmentally challenged adults have difficulty communication their needs; therefore, it is imperative that our programs are designed in a holistic manner.

Glossary

Adult Protective Service Worker (APSW) – a staff person to assist adults with case management, life skills, and general counselling. May provide some assistance with advocacy.

Association for Community Living (ACL) – A non profit organization working with people who have developmental disabilities. Parents and Families of people with developmental disability have worked together to provide support and services. It is governed by a Board of Directors committed to inform the community about the needs and aspiration of people with a disability and their families.

Autism – is a disorder of brain function that appears early in life- before the age of three. Children with autism have problem with social intervention, communication, imagination, and behaviour( they have a narrow and repetitive pattern of behaviour). The cause is unknown. Autistic traits persist into adulthood, but vary in severity. Some adults with autism function well, earning college degrees and living independently. Autism belongs to a family of related brain conditions af- fecting behaviour early in life.

Community Living Ontario – a Federation of Associations throughout the Province of Ontario having common goals advocating Provincially for individuals and their families.

Day Program – is about learning more about life skills and how to obtain those skills. Trying to en- courage employers to hire workers with disabilities by increasing their abilities for employment.

Developmentally handicapped (DH) – “ is a condition of mental impairment present or occurring during a person’s formative years, that is associated with limitation in adaptive behaviour” – DSA The condition is usually determined by a physician or a psychologist.

Continuum of Service – a full array of service delivery options in a specific program are i.e. residential care – SIL to 24hr/7 day a week one-on-one care.

Family Home Program – It is the Association’s responsibility to ensure that a Home Study and Written report are completed prior to finalization of approval as a placement for people. In order to promote the principles and goals of the Individualized Living Arrangements, no consideration will be given for the placement of more than two Clients in the same home.

Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS) – is a medical di- agnosis that refers to a specific cluster of anomalies associated with the use of alcohol during pregnancy. The three essential traits of FAS are prenatal and/or postnatal growth restriction, characteristics facial features and central nervous system involvement.

Fetal Alcohol Effects (FAE) – is a term used to describe children with prenatal exposure to alcohol, but only some FAS characteristics.

Group Home – is a MCCSS approved staffed, residence where 2 or more unrelated individuals reside.

Inclusion – is the term used to describe everyone living, working, and learning together, respecting each person as they are – including differences within one community.

Individualized Funding – Individualized funding refers to the allocation of public funds to individuals rather than to agencies or programs.

Individualized Living Arrangement (ILA) – the purpose of individual living arrangements is to de- velop and implement options for alternative living that will promote greater opportunities for development relationships between developmentally chal- lenged people and the community as a whole.

Individualized Support Agreements (ISA) – upon the development of a PCP there is a requirement by MCCSS to complete an ISA which stares who is providing what services and what cost to the person. It is to be signed by relevant parties.

Individual Support Worker (ISW) – The support worker is responsible for the overall supports and services through Person Centred Plan and the safety of the client and respect for the individual. The individual Support Worker is responsible for contributing to the overall well being and growth of each individual while being supported within the Association.

Integration – is the term used to describe people living within the community, but not being a part of it in the fullest degree.

Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services (MCCSS) – primary funder of DH services throughout the province – approximately 1 Billion dollars annually (2002 figures).

Person Centred Plan (PCP) – is a process which puts the individual and their family in control of organizing supports and services. It allows them, the opportunity to clearly state what they are expecting from supports they receive; to identify and over- come gaps and needs in the individual’s life and; to promote and ensure inclusion in community life. The facilitation of person centred planning will assist people to discover, actively plan for, and work towards a desirable future. Each person’s plan is unique and is deeply rooted in personal values, gifts and capacity.

Program Supervisor – an MCCSS employee responsible for service system coordination and delivery, normally through transfer payment agencies.

Respite Care – “Respite” refers to short term, temporary care provided to people with disabilities in order that their families can take a break from the daily routine of care giving.

Risk Management – the meeting of the individual’s needs while keeping in mind their best interest through the identification, analysis and response to identified risk factors.

Segregation – is the term used to describe people not involved in the community at all but operating in a parallel separate venue.

Services – refers to dollars expended to directly impact on the person’s improvement of intrinsic skills and/or for environmental and social ac- commodation that reduce the consequence of the condition. (Group Home, Day Program, SIL, SEP, Respite, Family Home, Clinical Treatment)

Special Services At Home (SSAH) – The goal of the SSAH Program is to help individuals with disabilities to live at home with their families. It helps them by providing individualized funding, on a time-limited basis, to purchase supports and services not available elsewhere in the community.

Supports – refers to the expenditure of dollars for indirect attainment of a person’s outcomes. (Case Management, Clinical Assessments, Mediator Model of Therapy).

Supported Employment Program (SEP) – Individuals with a disability that are willing to work paid by the employer. The Supported Employment worker maintains his or her services by ensuring that the individuals are comfortable and confident with his or her job.

Supported Independent Living (SIL) – is intended to provide intensive support and supervision for adults who are able to live in essentially indepen- dent settings with assistance from program workers on a visitation basis.

LOST AND CONFUSED

Choice, I have choice!

Words, that is all they are.

I have no choice, because,

My choice would be my home.

I’m lost in this strange place.

No familiar face I see.

I’m confused, I’m alone.

Help me, set me free.

I miss my people and the land.

I miss the laughter,

The music of my language.

I’m lost without my home.

Please, may I Have a choice.

To go back to my people,

To be cared for by my people,’

to once again feel loved.

To feel alive,

To laugh

To grow in my community.

This is what I choose.