There are many transitions in life. This Guide focuses on the transition to older adulthood for people with developmental disabilities. It is important to keep in mind that transition to older adulthood is not merely about accessing a variety of programs available to senior citizens. It is above all a planned and conscious evolution to embrace life as it presents itself during the aging process.

The Life Plan or Person Directed Plan

The Life Plan or Person Directed Plan of the individual provides the basis for the support provided by members of the support circle. As the person enters older adulthood, the life plan changes to include consideration of emerging issues and needs related to aging. Transition planning is not about replacing the Life Plan but provides a framework for thinking about and adjusting the Life Plan as the person ages.

The Role of the Individual in the Planning Process

The Task Group considered the role of the person with a developmental disability in the transition planning process. The person centred approach to planning requires that the individual be the source of information about their own life plan. The realization of this principle may be influenced by the person’s capacity to become involved and to make his/her needs known. Where there are limitations on capacity caregivers must rely on more on their personal knowledge of the individual. In all cases, the communications of the client however they may be expressed, are relied on to inform planning decisions.

Definition of Transition Planning

The Transition Task Group developed a definition of Transition Planning to Older Adulthood to help caregivers in their planning work. The definition can help to put all caregivers on the same page in their understanding of the transition planning process.

Transition Planning is a planned process that:

- Supports the individual in maintaining quality of life as he/she ages.

- Allows the individual to be the driving force in shaping the plan and to be involved in all plan-making to the extent of his/her capacity.

- Helps the person with developmental disabilities to plan for changes in their support needs as they age (aging is not necessarily related to a chronological age such as 65).

- May involve changes in how the family provides support or in the amount of support provided.

- May include access to day supports for older adults such as Meals on Wheels or a senior’s day program, so the person can remain at home, and / or

- May involve preparing for a move to a new residential setting where more appropriate support can be provided.

- Always includes the person with a developmental disability.

And may include a variety of people and organizations such as:

- The family, guardian or advocate.

- Friends of the individual.

- Direct care staff of a developmental services agency and / or older adult services agency.

- Facilitators and members of support circles.

- A case resolution coordinator.

- A medical practitioner and / or psychiatrist and / or psychologist.

- Coordinating bodies such as the local Community Care Access Centre.

- The Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services developmental services coordinated access process.

Checklist for Transition Planning

How comfortable are you and your planning group with the idea of Transition Planning?

- There is a clear idea of the transition planning process that all members of the support circle share.

- The group needs to meet to develop a common understanding of transition planning.

- We need more information about transition planning.

Getting Ready

The most important thing in supporting the individual and planning with them for their transition to older adulthood is to start early. It is very important to conduct an assessment prior to the onset of any aging symptoms. The results of this first assessment serve as a baseline and provide a point of reference for any changes that come later. There is no specific age to take a baseline assessment but the sooner the better. It is recommended that an assessment be done by the time the person reaches 40. However due to the prevalence of Alzheimer Disease among people with Down Syndrome and the tendency for its symptoms to show up earlier among this population group, in such a case a baseline assessment may be best done in the person’s early 30’s. Baseline assessments can include standardized tests conducted by professionals and baseline information can be kept in a life book that tracks changes with the person over time.

Checklist for Getting Ready

- Identify the age of the individual when you feel it would be best to begin planning _______.

- Gather and maintain history and background information on the individual.

- Create baseline data on the person prior to his/her entry into the years when the aging process accelerates.

- Acquire new skill sets related to support, intervention, health and emotional conditions associated with aging.

- Develop capacity to talk with physicians, specialists and other health practitioners and to keep a record of their diagnoses and treatments.

- Become aware of the full range of services available to older adults and how to access them.

- Get to know the contact people at the CCAC and all seniors programs/services; visit these programs to become familiar with what they offer.

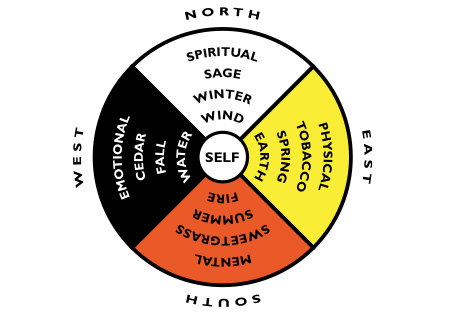

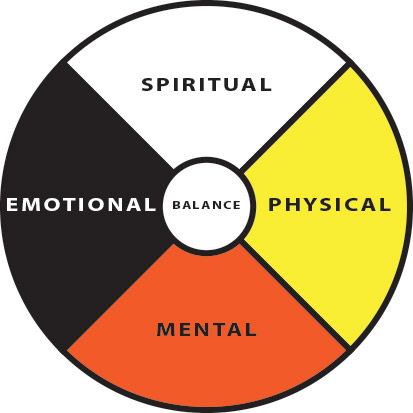

- Develop transition planning that encompasses the full range of the aging experience – physical, emotional, employment, decision-making.

- In the transition planning process, consider the impact that aging has on all other people in the client’s life (staff, roommates, friends, family) and how this may influence planning decisions.

- Ensure the individual’s plan includes clearly identified risk factors arising from family history, the presence of a syndrome, living situation and lifestyle.

Keeping A History

Because of the complexity of the aging process for people with developmental disabilities and the presence of different care givers and agencies in their lives over time, it is important to create and maintain a clear history. The history may include information about the birth, health conditions during childhood and the family history of illness that may predispose the individual to certain conditions (for example, diabetes or heart conditions). In many cases these records may be with the family or family physician. However it is important to assemble them in such a way that they are available to future potential caregivers in the event that a current caregiver is unable to continue in the care giving role.

Checklist for Creating a History

This checklist provides some guidance to thinking about the kinds of things that may be important to put into the history and where the items may be obtained.

- Birth history

- Family history

- Childhood illnesses

- Psychomotor assessments

- Psychological testing

- School assessments and reports

- Support agency assessments and reports

- Physician visits

- Specialist visits

- Immunizations

- X-rays

- Vision Check-ups

- Hearing Tests

- Dental Check-ups

- Special health conditions and needs

- Other ________________

Principles for Transition Planning

Support circles allow family, friends, neighbours and paid caregivers to work together in helping the individual realize his/her life plan. Transition planning to older adulthood may introduce new issues and additional caregivers from the long term care sector into this equation. The Transition Task Group believes that support circles can be helped in their work by adopting principles to guide their interactions and decision-making. Your circle may have developed its own guidelines or philosophy. However the Task Group found the following set of principles helpful to think through the issues that arise with aging and to provide a point of reference when new members enter the circle.

These principles were developed by the Huron Trillium Partnership. The partnership was formed by developmental service and long term care providers as well as coordinating and planning bodies in Huron County. They created the principles as a result of their transition planning experience with older adults who have developmental disabilities. They are provided here to help you think about some of the key aspects of transition planning.

- Respect for the Individual

Each person is unique in his or her abilities, preferences, emotional nature, physical characteristics and learning. Transition Planning should respect the dignity of the supported individual and ensure that plans reflect their needs and aspirations. Moreover plans should support the rights of each individual under the Canadian

Constitution, the Ontario Human Rights Code, the Ontarians with Disabilities Act and other government

legislation. - Family Involvement

The relationships that each person may have with members of his/her family are to be encouraged and respected. Transition Planning should always allow for the inclusion of family or other significant people in the individual’s life and in the Transition Planning Process. - Continuity of the Life Plan

Transition Planning is not a substitute for life planning but an integral part of it. Transition Plans should consider how to uphold the person’s pre-existing life plans and be attentive to the whole person. - Respect for All Relationships

People vary in their capacity to form relationships and to engage in the many aspects of relationship-building.

Transition Planning should allow each person to form and to enjoy relationships with others, both persons with and

persons without an intellectual disability. - Valuable Community Involvement

Transition Planning should consider every aspect of community life:- Social relationships

- Recreation, education, employment, self-improvement groups, leisure activities

- Participation in a worship community

- Citizenship roles such as voting, participation in political processes, access to elected representatives and involvement in civic affairs.

- Balance of Risk with Safety

The pursuit of goals in life is often accompanied by risk. Transition Planning should allow for risk while ensuring the person does not put themselves in danger. - Communication

Persons with a developmental disability may have different ways of communicating with others. This may include eye contact, sounds, motions, phrases and complete sentences. Transition Planning must include careful listening to each message in whatever format it is offered. In this way respect may be assured for the dignity and wishes of the person. Moreover, it is important to inform new caregivers who become part of the person’s support system about their unique communication methods and messages.

Sourced from “Transition Guide For Caregivers”, The Ontario Partnership on Aging and Developmental Disabilities http://www.opadd.on.ca