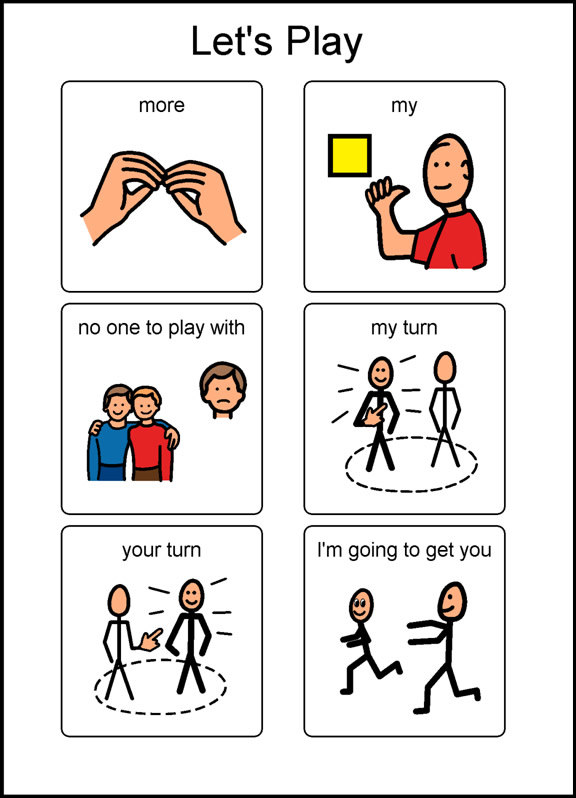

Some children find it easy to join a group of children. When they see another child, or a group of children playing something that looks like fun, they either just sit down and join in, or ask simple questions such as, “What are you doing?”, or “Can I play?”.

For some children, joining in a game can be very challenging. These children might play alone or use inappropriate methods of joining in, such as grabbing toys, or hitting other children in order to get their attention. None of these strategies are appropriate. The child who grabs or hits will probably be seen as a “trouble maker” and is unlikely to be welcomed into the play group. A child who does not join in, but stands alone on the sidelines might be feeling very lonely or shy. They also are not learning all the important skills that group play can teach.

Like other social skills, the skill of “joining in play” is one that some children can be taught – step by step.

Helping your Child Learn How to Join in Play

As a parent, teacher or early childhood professional, you can help your child learn how to join in play using the following ideas.

-

- Talk about it

Start by talking to your child or children about the specific skill. Ask her questions like:“How can you ask a friend to play? Show me.”em>

“How does it feel when you play with someone else?” - Teach

You can teach your child about the appropriate ways to join in play. One tool you can use is a personal story.The goal of a personal story is to:

- describe social situations that are difficult for your child,

- increase his understanding of this situation,

- provide suggestions about how to behave, and

- give your child some perspective or understanding on the thoughts, emotions, and behaviours of others.

It is best to use a personal story when your child is calm and focused, not when the challenging situation is actually happening. Try reading and talking about the story daily (perhaps at the beginning of the day) so that your child is able to really understand.

- Talk about it

- Role-Playing

Role-playing consists of acting out various social interactions that children would typically encounter. Puppets or other toys can also be used as “actors” in the role-play.Role playing teaches children the actual words they can say and the things they can do in specific situations. It also gives children an opportunity to practice these new skills with their peers.

In the beginning, you should play all the ‘parts’ to show your child what she can do or say in certain situations. You can keep her interested by using characters from her favourite television shows. Be sure to speak in an animated voice and use words that your child can understand.

Try to act out situations with both positive and negative responses, as this will help your child understand that other children are not always willing to share or play with her.

Here are some examples:

Scenario 1

Dora and Boots are playing with blocks. Swiper comes close, taps Dora on the shoulder, makes eye contact, and says, “Can I play with you?”

Dora says, “Sure”. Swiper says, “Thanks” and joins the game.

Scenario 2

Dora and Boots are playing with blocks. Swiper comes close, taps Dora on the shoulder, makes eye contact, and says, “Can I play with you?”

Dora says, “No”. Swiper says, “OK” and goes to find someone else to play with.

Steps to take when using role-playing to teach children to join in play:

- Step 1 – Model the skill

Two or more adults model a situation in which one asks the other to join him/her in play. The specific phrases and behaviours that your child needs to learn are modelled.Role-play a few possible scenarios so that children are prepared for different situations:

Scenario 1

Person A and Person B are playing with blocks. C comes close, taps A on the shoulder, makes eye contact, and says, “Can I play with you?”

A says, “Sure”. C says, “Thanks” and joins the game.

Scenario 2

Person A and Person B are playing with blocks. C comes close, taps A on the shoulder, makes eye contact, and says, “Can I play with you?”

A says, “No”. C says, “OK” and goes to find someone else to play with.

- Step 2 – Select role players

At first, it is best to have older children or ones who are more experienced at the skill do the role-play and have your child watch and comment.

If possible, give all interested children a turn to do the role-play. It is especially important that your child who is learning the skill has a turn to be part of the role-play. - Step 3 – Children do the role-play

A small group does the role-play and the other children watch and comment.After seeing a few examples, your child can be part of the role-play. She should play many different parts in the role-play.

Encourage the children to role-play different scenarios and outcomes (e.g., when someone says, “No, you can’t play with us.”)

- Step 4 – Provide feedback

Everyone can give feedback to the role-players. Remember, you are modeling how to give positive feedback. Give specific, positive feedback to all children involved in the role-play. For example, “I liked how Joshua asked Amelie if he could use some of her crayons.”

- Step 1 – Model the skill

- Reinforce

Tell your child that you will be watching for this skill for a week. Reinforce your child when you see her joining in play and remember to label the behaviour that you want to see.“Bernice, good job using words to ask to play with Christopher”.

- Review

Talk about the skill for a few minutes each day so that it is fresh in your child’s mind. This also helps her understand the importance of this social skill.Teaching your child how to join in play can be challenging and takes time. You will be most successful when you are:

PATIENT – Some children might need more reminders, more support, and more time to learn.

CONSISTENT – Make sure that you and any other adults in your child’s life have the same expectations of the child.

POSITIVE – Remember to look for your child using the skill and reinforce her as much as possible.

By using these strategies and encouraging your child, she will become more comfortable joining in play with other children.

Source:

Personal stories are based on “Social Stories” created by Carol Gray.