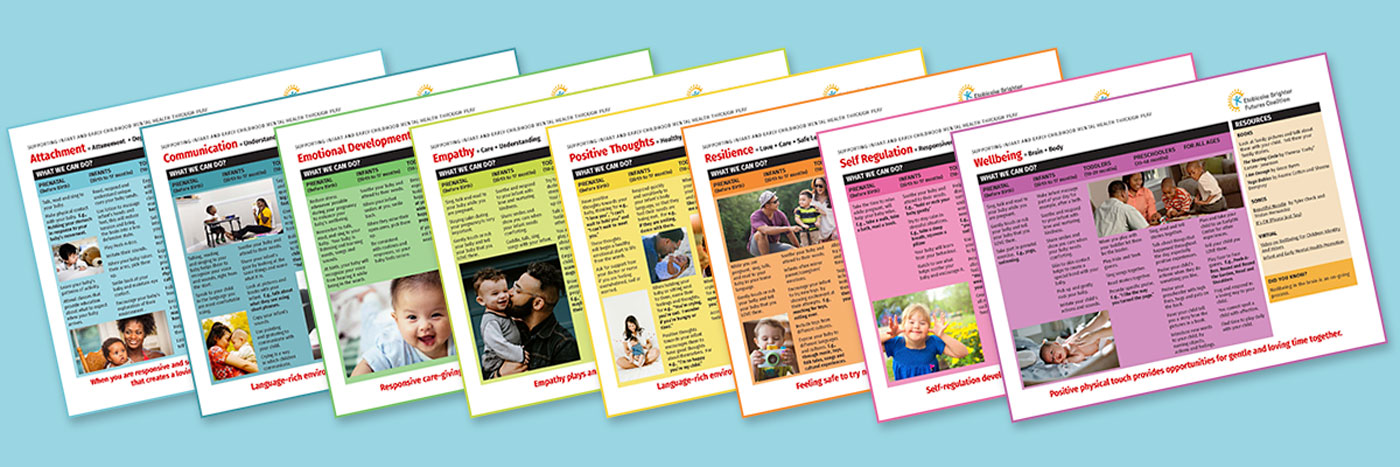

Attachment

Play video

Play video

Attachment = Attunement + Dependability

When you are responsive and sensitive to what your baby “serves”, you can form a “return” response that creates a loving and supportive environment that children can thrive in.

Communication

Play video

Play video

Communication = Understanding + Expression

Language-rich environments are the foundation for future learning success.

Emotional Development

Play video

Play video

Emotional Development = Recognition + Attention

Responsive care-giving establishes the foundation of emotional development.

Empathy

Play video

Play video

Empathy = Care + Understanding

Empathy plays an important role in the development of social skills.

Positive Thoughts

Play video

Play video

Positive Thoughts = Healthy Experiences + Supportive Environments

Positive thoughts can help build positive self esteem

Resilience

Play video

Play video

Resilience = Love + Care + Safe Learning Opportunities

Feeling safe to try new things promotes the ability to deal with obstacles.

Self Regulation

Play video

Play video

Self Regulation = Responsiveness + Role Modelling

Self-regulation develops when adults respond sensitively to a child’s needs.

Wellbeing

Play video

Play video

Wellbeing = Brain + Body

Positive physical touch provides opportunities for gentle and loving time together.

We thank the team of dedicated professionals in the Etobicoke Brighter Futures Coalition that developed these IEMH Play Statements.

All rights reserved by the EBFC